How a Blooming Career Took Root: Dr. Margaret Pooler

Dr. Margaret Pooler, who serves as Research Leader of the U.S. National Arboretum’s Floral and Nursery Plants Research Unit (FNPRU), counts herself lucky that she came across her job as a shrub breeder — a position now known as a woody ornamental breeder. “You can imagine when you’re making crosses on a beautiful spring day; cherry blossoms are falling around you, and the bees are buzzing. It’s just magical.”

When Pooler graduated from the University of Wisconsin in 1991 with a Ph.D. in plant breeding, she assumed she would pursue a career in breeding food crops. “I didn’t think that I would be fortunate enough to work in ornamental plants because that didn’t seem to be where most of the breeding jobs were.”

After spending her early career at the U.S. National Arboretum (USNA) breeding new plants and helping bring in new technologies, Pooler moved into the Research Leader position for what she thought would be a short stint. She had been reluctant to trade her time in the field for a more administrative role. The switch led Pooler to tap into one of her superpowers, “I feel like I’ve really found what I’m even better at than doing science. It’s advocating for and supporting science.”

Pooler has built an impressive and productive career during her tenure at the USNA. “Margaret is a superstar. She is both an excellent scientist and a scientific leader,” says Dr. Thomas Ranney, who leads a horticulture science research laboratory at North Carolina State University. Ranney has known and worked with Pooler since the 1990s. “We have collaborated on various projects including the development of seedless, non-invasive nursery crops and the development of new biotechnologies for crop improvement, including gene editing technologies.”

Currently, Pooler oversees the Arboretum’s research projects, which include plant pathology, breeding, taxonomy, plant production, turf genetics, and genetic resource conservation. For her own research projects within the FNPRU, she and two other scientists work with a talented and dedicated support team to develop improved woody ornamental plants and associated breeding technologies that will benefit both the nursery and landscape industries and the public. The overall focus is to develop plants that are hardier and more resilient to climate fluctuations, diseases, and pests.

“I think people underestimate how important ornamental plants are, or what impact they have on the U.S. economy. I also think they underestimate the value of what ornamentals, and more broadly the whole green industry, have on the environment, human health and well-being.” Pooler points to the ornamental and landscape plant industry’s hearty $4.5 billion contribution to the U.S. economy. The green industry benefits from research that is conducted at the Arboretum.

Although Pooler says that she spends most of her time supporting her colleagues so they have the resources they need to conduct their research, there is no doubt she has been integrally involved in USNA breeding and the release of numerous ornamental plants. These include cultivars of flowering cherries Helen Taft, a Yoshino cherry with clear pink blooms, and First Lady, prized for its upright form and very early dark pink blooms; lilacs Betsy Ross, Old Glory, and Declaration, adaptable to warmer locations; Nantucket viburnum; and crapemyrtles Arapaho and Cheyenne, the first nearly true red-blooming hybrids, and the more compact Pocomoke.

From left: Prunus ‘Helen Taft’, Prunus ‘First Lady’, lilac ‘Betsy Ross’, lilac ‘Old Glory’, lilac ‘Declaration’, viburnum ‘Nantucket’, crapemyrtle ‘Arapaho’, crapemyrtle Cheyenne’, crapemyrtle ‘Pocomoke’. Photos courtesy of the U.S. National Arboretum. Click each photo to view in full screen.

Additionally, Pooler’s research has led to the development of rapid tests to detect the presence of and resistance to fungal species that cause diseases like boxwood blight. Boxwood blight causes lesions on the leaves and stems of boxwood plants, which can eventually lead to them dying.

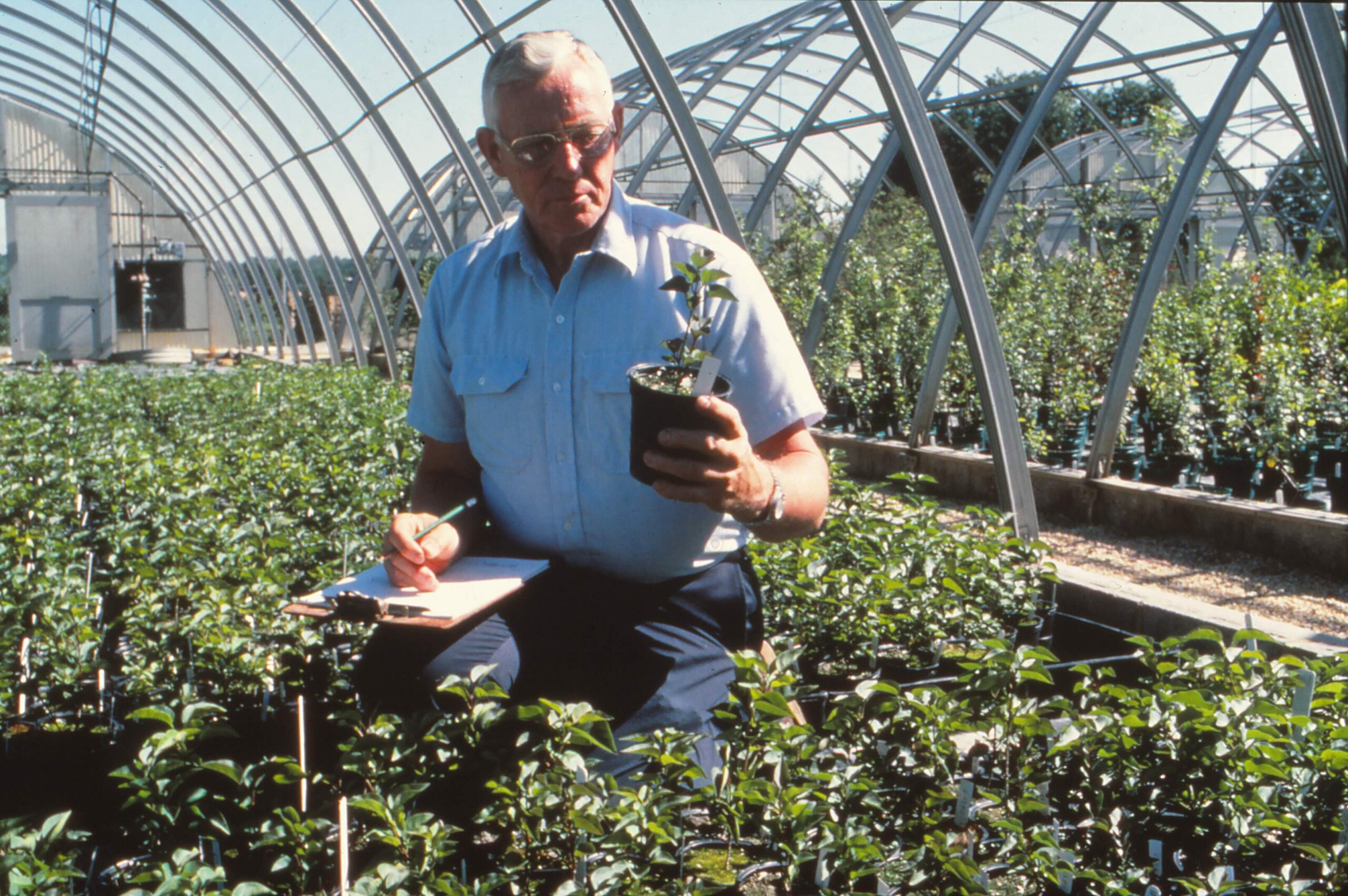

Pooler credits her predecessor, the late Dr. Donald Egolf who was a renowned USNA horticulturist, for setting her up for success. Even though she never met him, Pooler said his breeding accomplishments and meticulous records were invaluable. The vast majority of her program’s woody ornamental releases were hybrids derived from Egolf’s breeding efforts over four decades at the Arboretum. “If I had come into another program that I had just started from scratch with nothing, it would have been a totally different career for me. It would have been much more frustrating and less productive if I didn’t have that material in place. I was very fortunate to have those shoulders to stand on.” In July 2000, Pooler led the release of the National Arboretum’s first redbud cultivar, naming it Don Egolf in his honor. It has a prolific spring bloom but is fruitless and has exhibited no invasive tendencies.

Pooler’s role as Research Leader has allowed her to mentor and support other scientists, students, and postdocs while leading large interdisciplinary teams that tackle long-term projects. Dr. John Hammond is a Research Plant Pathologist at FNPRU and has worked with Pooler for almost 30 years. He says Pooler excels at building cohesive teams that work nearly seamlessly together. “She is very approachable. She’s a good listener. She also makes efforts to keep everybody afloat.”

Under Pooler’s leadership, the FNPRU lab has seen a 60% increase in base funding, plus success in procuring competitive grants. This has been critical, particularly during a time when researchers find themselves competing for limited funds. “I’m most proud of being able to support the kind of research that we’re doing and keep it moving forward,” she says.

Ranney and Hammond praise Pooler’s work and accomplishments as impactful and relevant. “She has been instrumental in utilizing and integrating molecular biology in the study and improvement of landscape plants,” Ranney notes. “This has included the use of molecular markers for plant breeding, studies on genetic diversity and relatedness, research on pathogens, conservation biology, and more.” Such work enables scientists to be more precise and shortens the amount of time it takes to get results, and there is a long-term effect, Ranney adds, “Overall, these efforts enhance the environment, grow agricultural economies, and enhance our quality of life.”

Pooler urges people to recognize the important function plants and plant science play in our world. “Some people don’t think about what would happen if we took away half of the species of plants that we have today. It would be devastating.” She adds, “The Arboretum plays a key role in helping people recognize and value the importance of plants to our well-being. People tend to think about plants in terms of beautifying a landscape or as a Mother’s Day gift. We hope that they will be inspired to gain a deeper understanding and appreciation of how remarkable the plants around them are.”

After dedicating her career to horticulture, Pooler shares this advice for early career scientists navigating their professional journey: “If you’re offered a seat at or near the table, take it. Don’t assume that you’re not qualified or the timing isn’t right or that it’s not going to be something you like. Often you can grow into it or change it to be the perfect situation.”

Bridget DeSimone is a communications consultant and writer for Friends of the National Arboretum. She is an experienced public relations professional and journalist who has worked extensively with scientific researchers and nonprofit organizations.